Share your craft projects

Make new craft buddies

Ask craft questions

Blog your craft journey

Brit

478 posts

and

40 followers

in over 11 years

in over 11 years

More from Brit

YouTube makes me laugh

Beginner's Guide to Sharpening Western Saws

The Humble Hand Brace - A Beginner's Guide to Restoring, Buying and Using #8: Part 8 - Tips and Tricks on Using a Hand Brace

The Humble Hand Brace - A Beginner's Guide to Restoring, Buying and Using #7: Part 7 - Sharpening an Auger Bit

The Humble Hand Brace - A Beginner's Guide to Restoring, Buying and Using #6: Part 6 - What to Look for when Buying a Secondhand Brace and more

The Humble Hand Brace - A Beginner's Guide to Restoring, Buying and Using #1: Part 1 - Restoring a Brace to 'Like New' Condition

This is

part 1

in a

8 part

series:

The Humble Hand Brace - A Beginner's Guide to Restoring, Buying and Using

-

Part 1 - Restoring a Brace to 'Like New' Condition

-

Part 2 - Cleaning and Restoring a Brace to 'Like New' Condition

...

- Part 1 - Restoring a Brace to 'Like New' Condition

- Part 2 - Cleaning and Restoring a Brace to 'Like New' Condition

...

In a tool gloat, someone on a different forum showed off some lovely braces he'd purchased and said "Now I just have to learn how to restore this kind of thing". He said he would love to restore at least one of them to like new condition. Always a sucker for punishment, I agreed to do a blog on restoring a hand brace and I've selected the worst hand brace of the three I have waiting for love. Here's how I see this blog going:

• Parts 1 to 4 - Cleaning and restoring a brace to 'Like New' condition.

• Part 5 - Tuning - Common problems and how to fix them.

• Part 6 - VIDEO - Showing variations in design and what to look for when buying a brace.

• Part 7 - VIDEO - Uses for a hand brace in today's workshop.

• Part 8 - Auger bits and how to sharpen them.

Let me say at the outset, that the kind of brace we'll be discussing is the kind your father and grandfather would have used prior to the advent of the electric drill and later the cordless drill. I won't be discussing older metal braces such as the Spofford brace or Scotch brace, or any of the earlier wooden braces. No, the braces we'll be looking at are the ones you are most likely to find covered in cobwebs at the back of a garage, in the rust pile at a flea market, or hanging on the walls of a trendy wine bar.

I should point out before we start that there are as many different approaches to tool restoration as there are people who restore old tools. For me, the most important thing is FUNCTION. A tool should work as designed and perform well. However I also like my tools to look nice, so a close second to function is that they are AESTHETICALLY PLEASING and TACTILE. I want my tools to say "Pick me up and use me". With the vast majority of braces, this means removing some surface rust, a gentle clean, lubricating the moving parts and refinishing the wooden parts. I usually don't try to get them to look like new. In fact, I like to leave a few war scars here and there to hint at the tool's history.

All of the braces that I've restored in the past have been done in no more than 24 man hours, spread over a few days to allow multiple coats of finish on the wood. One other thing to note is that I won't be using any power tools or machinery during this restoration. The metalworking hand skills you'll see employed here, are basic skills that you would do well to practice. You should look at this restore as a worst case scenario. In reality, you probably WON'T need to employ all of the steps you'll see me perform. Use your judgement as to which steps are appropriate for your brace restoration project.

So without further adieu, let me introduce you to RUSTY, an 8" sweep brace made by Skinner of Sheffield.

• Parts 1 to 4 - Cleaning and restoring a brace to 'Like New' condition.

• Part 5 - Tuning - Common problems and how to fix them.

• Part 6 - VIDEO - Showing variations in design and what to look for when buying a brace.

• Part 7 - VIDEO - Uses for a hand brace in today's workshop.

• Part 8 - Auger bits and how to sharpen them.

Let me say at the outset, that the kind of brace we'll be discussing is the kind your father and grandfather would have used prior to the advent of the electric drill and later the cordless drill. I won't be discussing older metal braces such as the Spofford brace or Scotch brace, or any of the earlier wooden braces. No, the braces we'll be looking at are the ones you are most likely to find covered in cobwebs at the back of a garage, in the rust pile at a flea market, or hanging on the walls of a trendy wine bar.

I should point out before we start that there are as many different approaches to tool restoration as there are people who restore old tools. For me, the most important thing is FUNCTION. A tool should work as designed and perform well. However I also like my tools to look nice, so a close second to function is that they are AESTHETICALLY PLEASING and TACTILE. I want my tools to say "Pick me up and use me". With the vast majority of braces, this means removing some surface rust, a gentle clean, lubricating the moving parts and refinishing the wooden parts. I usually don't try to get them to look like new. In fact, I like to leave a few war scars here and there to hint at the tool's history.

All of the braces that I've restored in the past have been done in no more than 24 man hours, spread over a few days to allow multiple coats of finish on the wood. One other thing to note is that I won't be using any power tools or machinery during this restoration. The metalworking hand skills you'll see employed here, are basic skills that you would do well to practice. You should look at this restore as a worst case scenario. In reality, you probably WON'T need to employ all of the steps you'll see me perform. Use your judgement as to which steps are appropriate for your brace restoration project.

So without further adieu, let me introduce you to RUSTY, an 8" sweep brace made by Skinner of Sheffield.

Skinner braces were not 'high end' tools, just simple workhorses that the working men of England would have used. As you can see, this one has certainly seen better days. By the way, that dark brown colour is NOT a nice patina, its rust. Let's take a closer look at the ratchet and chuck. We've got RUST, scratches, RUST, dings and dents, RUST, paint splashes, and more RUST. OMG, what have I let myself in for?

The English beech wooden head and sweep handle aren't actually that bad when you consider what the metal is like and they still retain most of their finish. I will be refinishing them however, in our quest for the 'like new' condition challenge.

Here you can see the aluminium end caps of the sweep handle which a number of manufacturers incorporated into their braces. You'll only find it used on parts that don't contribute to the strength of the brace, typically the sweep handle end caps and sometimes the ratchet selecter. Just remember to take it easy when you restore the aluminium bits, as it is a lot softer than steel.

Now we've had a good look at our subject, its time to dismantle it ready for cleaning. The first step is to unscrew the chuck until it is completely off. The jaws should come off with the chuck. Now insert a finger (whichever one will fit) or a piece of dowell in the business end of the chuck and push the jaws to the other end of the chuck housing (knurled end in this case). They should stick out just enough for you to grab them with your other hand and gently wiggle them over the internal chuck thread and out of the housing.

Here you see the chuck and jaws removed. As far as I'm aware, all of the chucks found on braces of this era had two jaws. Some of them (like this one) had zig-zag teeth to help the jaws align properly as the chuck was tightened. These are generally referred to as aligator jaws for obvious reasons. Alligator jaws can grip round, square tapered and hexagonal shanks. The jaws fit into the slot in the threaded portion of the ratchet mechanism which prevent the jaws from turning with the chuck housing. If you now stick your finger in the other end of the chuck housing (the knurled end in this case), you'll feel that the internal diameter of the chuck reduces in size the closer you get to the end where the jaws would normally protrude. As the chuck is tightened, the curved sloping faces of the jaws ride on this internal surface, forcing the jaws together and gripping the bit tight.

Now let's turn our attention to the Head. There are usually two or three screws securing the wooden head to the brace body. Unscrew them and the head should fall off in your hand. Be ready to catch it!

If it doesn't, DON'T start hitting it with a mallet. Some heads are screwed on to the metal (like the one shown below), with the female thread being cut into the wood itself. Grip the metal part in one hand and the head in the other hand and unscrew the head. If it still doesn't want to come off, it is probably best to leave it in situ, so put the screws back in and mask up the wooden head to prevent it getting damaged while you're cleaning the metal.

For most braces, that is as far as you need to go in terms of dismantling them.

Now its time to commence cleaning, starting with the metal components. Its best to leave the wood until last, as cleaning metal can get messy and you'll only spoil any finish you put on the wooden components. Everyone has their favourite way of cleaning metal and that's fine by me as long as it works. Below, you can see the products that I generally use. A degreaser, 0000 steel wool, and a good general purpose light oil that lubricates, cleans and prevents rust. There is also a rust remover gel, a roll of absorbent paper towel, an old tooth brush, a scouring pad and a pin. I will also be using a soft wire brush (don't use a stiff one) and some P240, P400, P600, P800, P1200 wet and dry paper. Just to reiterate what I said earlier, use your judgement to determine which of these things you need to use. Depending on the condition of your brace, they might not all be necessary for your restoration.

I start by cleaning the chuck and jaws. Before I attack the rust, I like to use a degreaser. Rust remover works better after degreasing. Give the can a shake and spray on the foam. Most degreasers are citrus based, so while the foam is working it's magic, take a moment to savour that lemony limey odour.

After 5 minutes, I scrub the entire surface with a toothbrush (don't forget the inside of the chuck).

Then I rinse them off in a bowl of water and dry them thoroughly with a paper towel.

Now its time to start tackling that rust. I'm using a gel, but you could also use a dip (if you're in the US, try Evapo-Rust). Some people also favour electrolysis, citric acid or even naval jelly. There are lots of ways to remove rust, you just have to find what works for you. I liberally apply the gel inside and out with a toothbrush and leave it to work for 20 minutes (other products may differ).

When the time is up, I scrub the surface with the scouring pad and soft wire brush (yeah I know I need a new one), to remove all the rust that wants to come off. If it doesn't want to come off, don't force it.

Below you can see how the components looked after the first application of the gel. The rust has gone from the jaws, but the chuck will need another go. Heavily rusted components such as these, will usually require two or three applications of the gel before all the rust is gone.

I apply more gel and leave it to work for 15 minutes.

While the chuck is cooking, I examine the condition of the jaws. As you can see, the curved surfaces that ride on the inside of the chuck are badly scored and this will need rectifying.

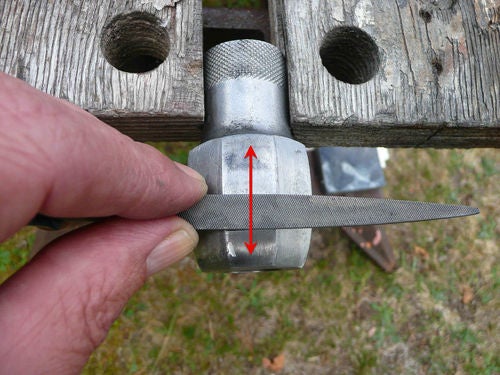

I grabbed a flat file and filed the surface until all the marks were gone.

The ends of the jaws were also in need of attention, so I take the time to file those flat too.

I put the jaws aside and scrub the chuck some more with the wire brush and scouring pad. Then I rinsed it off and dried it. This is how it came out.

One side doesn't look too bad, but the other side is a different story. Yes it's the scourge of any tool restorer - PITTING. A little bit of pitting is Ok, but the challenge is to get it 'like new', so it will have to go.

Using a small flat file, I file along the length of the three flats that are pitted, taking care to follow the curvature of the surface. I only remove as much metal as is necessary.

After about 10 minutes, the pitting has all but gone from the three surfaces, but now I have coarse file marks instead.

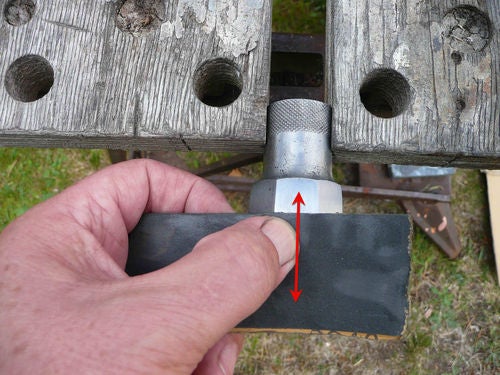

To remove the file marks, I draw-file the surface. For those of you who are not familiar with draw-filing, you apply a drop of oil to the surface, hold the file perpendicular to the surface with both hands. Then work it back and forth along the length of the surface until you have an even scratch pattern. Keep your hands close together and let your fingers ride along the adjacent surfaces to keep the file level.

Here you can clearly see the difference between the draw-filed surface on the right and the coarse filed surface on the left.

After draw-filing the other two surfaces, I put the file aside and turn to the wet and dry papers.

I start with P240 grit and work through the grits up to P1200 on each of the three surfaces. Sanding metal is the same as sanding wood. I work in one direction only and use each grit to remove the scratch pattern left by the previous grit.

I finish by polishing the surface with 0000 steel wool. I like the way it looks but the only trouble is, now I've polished the three faces that were heavily pitted, the adjacent faces look awful in comparison. At this point, as you can see from the reflection in the surface and the droplets of water, the good old English weather decided it was time for a coffee break.

There was nothing else for it but to do the other faces too and bring them up to the same standard. Same process as before.

So here's the finished chuck - well almost. I've still got to smooth out the inside a bit to get rid of the roughness that caused the gouging on the jaws. I'll show you how I do that in Part 2 where I'll also clean the rest of the body. In the meantime, I'm off to buy a new wire brush.

Thanks for looking.

Andy -- Old Chinese proverb say: If you think something can't be done, don't interrupt man who is doing it.

1 Comment

Nice read Andy, I have a few that could be restored some day.

Main Street to the Mountains

More from Brit

YouTube makes me laugh

Beginner's Guide to Sharpening Western Saws

The Humble Hand Brace - A Beginner's Guide to Restoring, Buying and Using #8: Part 8 - Tips and Tricks on Using a Hand Brace

The Humble Hand Brace - A Beginner's Guide to Restoring, Buying and Using #7: Part 7 - Sharpening an Auger Bit

The Humble Hand Brace - A Beginner's Guide to Restoring, Buying and Using #6: Part 6 - What to Look for when Buying a Secondhand Brace and more